We did this thing for Joseph.

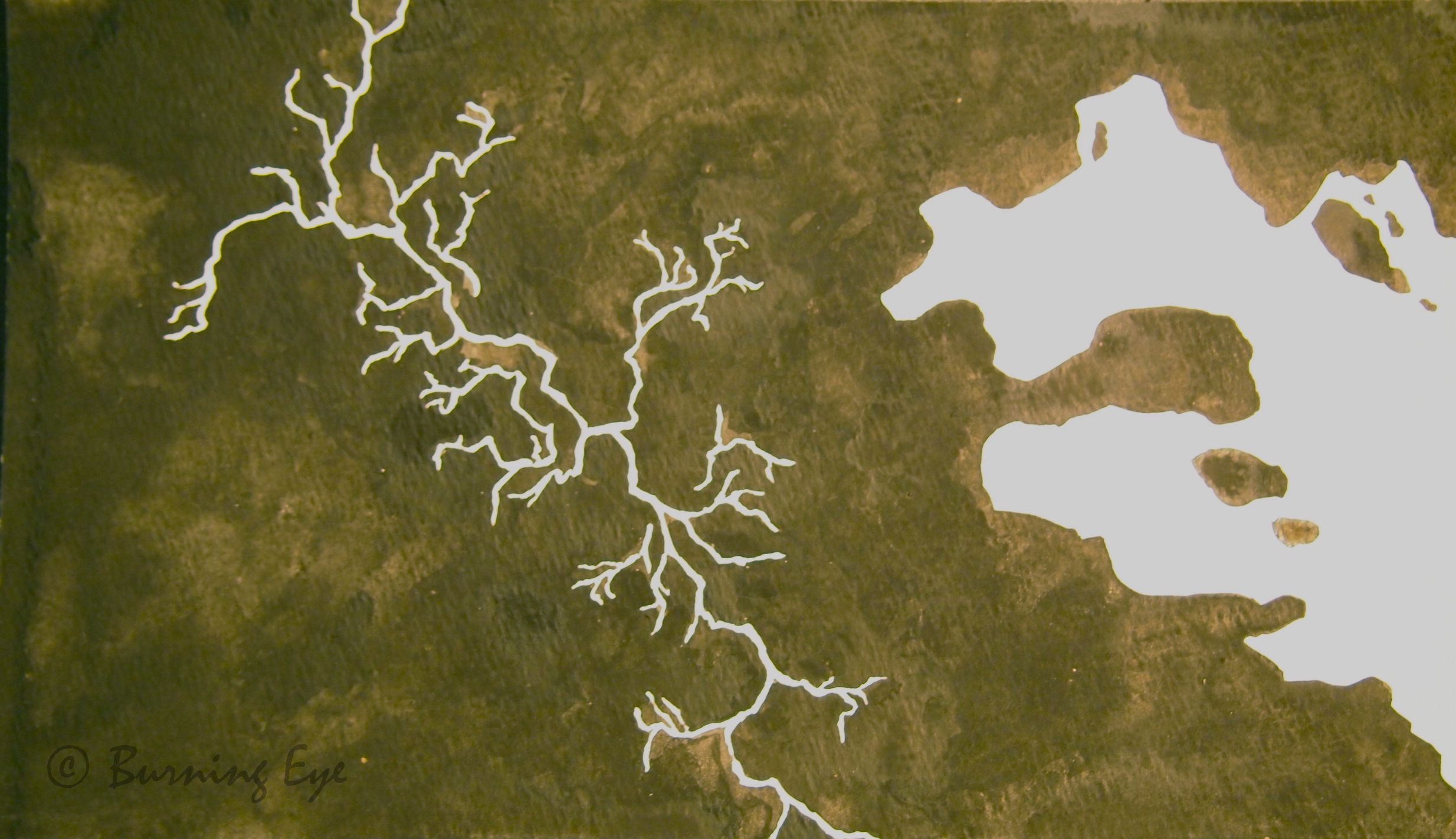

On a cold, sunny day last weekend, we invited some friends and family over to help us yarn bomb the backyard. They came and we put yarn needles in their hands and they crouched down in odd positions or climbed step ladders to sew color all over the trees. Even some of the younger kids helped. And it came together just like we’d planned. The barren yard, the winter trees, the grey and brown and shadows, are bright with rainbow patchwork colors.

This was the culmination of a year-long project. On Joseph’s ninth stillbirthday, we had invited everyone to send us yarn throughout the year: crocheted, knitted, woven. Crooked, uneven, and imperfect, or practiced and masterful. Any size, any color. Pieces came to us throughout the year, as did skeins of yarn, sometimes left on our porch in a bag, and once, serendipitously, brought to my classroom after a coworker acquired someone’s whole stash.

I learned how to crochet, and I crocheted all year. I spent more time untangling yarn and wrapping up tail ends of yarn than I ever thought possible. I carried yarn in my purse, yarn on vacation, filled a box with yarn that sat next to me at the dining table. This year, the yarn has become Joseph, in the way that collaging and charcoal sketches, painting or Christmas ornaments have all taken their turns as him.

Bit by bit as friends mailed us their contributions, we went out into the yard to see where they fit. I diagrammed and labeled tree branches, tacked things up temporarily with sticks and took photos. I stitched squares and rectangles together in long scarves, or took big scarves apart and sewed up the loose ends. Then I pinned on coded labels and rolled them up neatly, stuffed them in bags in the closet.

I felt a little tender, a little raw, to work on such a public project like this. Not just to share it with friends and family, but to bring Joseph’s anniversary out from many years’ quiet observance into the light of community. To crochet publicly, to turn our corner lot into a bright installation open for anyone passing by, meant that I talked about Joseph all year.

I shared his story at school with new coworkers that I might not ever have mentioned my firstborn to. I brought him up to people who knew me then but hadn’t acknowledged the loss in years. I heard from distant friends I hadn’t spoken to in decades. A few friends shared Joseph’s story with other friends they knew in order to commission a piece for the project, because they themselves don’t knit.

I told my second-graders about Joseph, about the yarn. They would see me crochet at recess or during car-rider duty and ask me what I was making. A sweater for a tree, I would say. Or simply, a rectangle, a flower, a square.

He died before you were even born, I told the seven- and eight-year-olds, and they gaped, eyes wide. To a child, their whole short life is forever. To them, these ten years are as impossibly long as they feel to me.

He would have been 10, I told them. But I know that’s not exactly right. I still cannot think of Joseph in would-have-beens. I can only mark the time as it passes. I can only count the skeins of yarn, the number of circles and hexagons my fingers have knotted.

It has been 10 years since my baby died, since we named him, since he became memory. And this year, he has become colors and material and stitches, shapes and circumferences and trees.

I wanted the yarn bombing to have an end, a date complete. But all week we have been taking more pieces outside, extending the color up and out as the limbs branch and spread. And now today is your day and we still have two bags left, could still do more. My fingers itch to unravel and loop, hook and pull.

I think today I have finally made peace with this, with the undefined boundaries of the project. It will continue to evolve and change into the new year without a final point, the way that Joseph has no end, no finite impact in our lives.

(C) Burning Eye